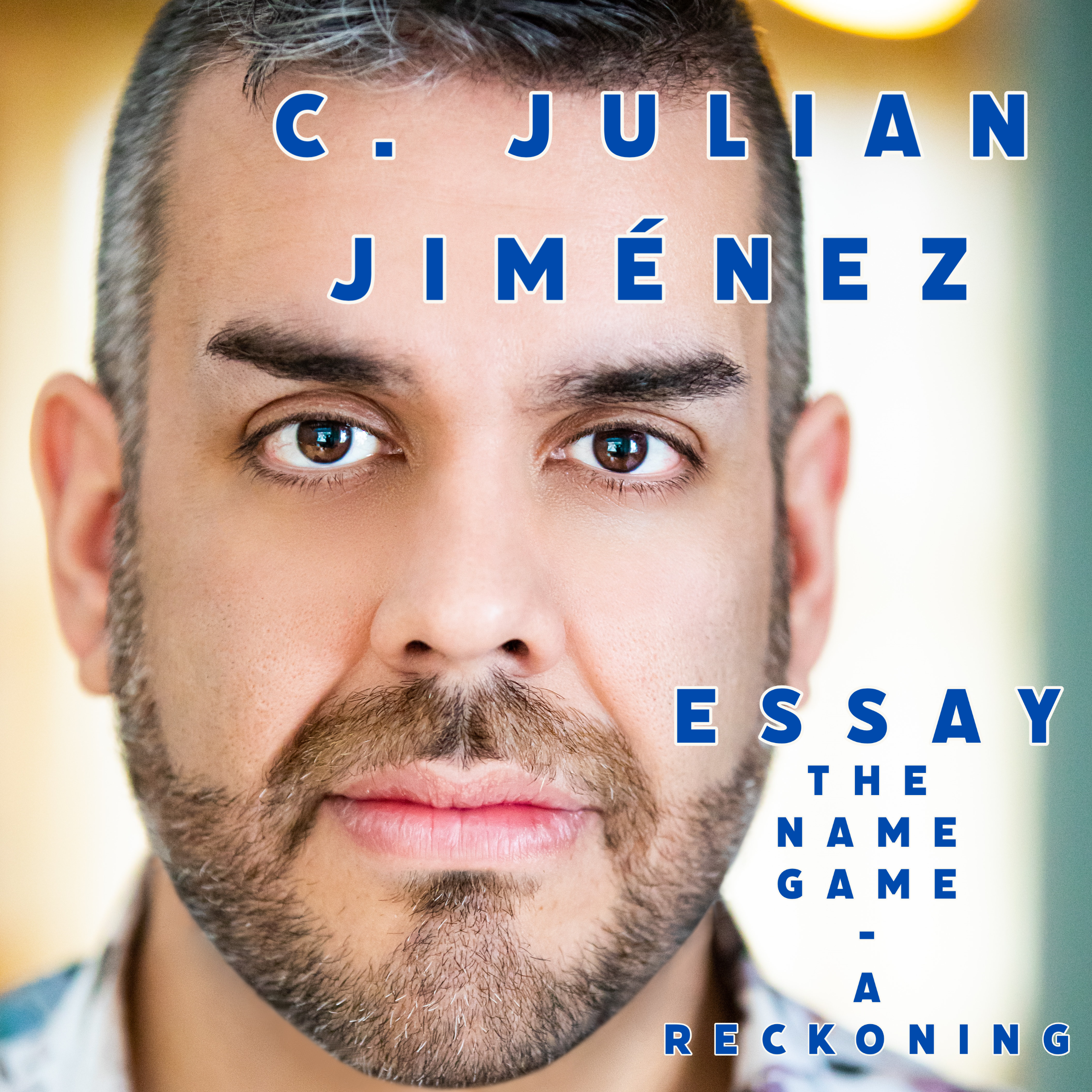

essay

THE NAME GAME - A Reckoning

by

J̶.̶ ̶J̶u̶l̶i̶a̶n̶ ̶C̶h̶r̶i̶s̶t̶o̶p̶h̶e̶r̶

C. Julian Jiménez

Nothing made my father laugh harder than Bill Dana’s character, José Jiménez, from Make Room for Daddy and subsequently, The Bill Dana Show.

“My name… José Jiménez.”

Dana’s broken English catchphrase made white people laugh and laugh. My father laughed as well, not wanting to be labeled as “that kind of Latino.” His name being Julian Jose Jiménez didn’t help. Unlike how it’s pronounced in Dana’s famous catchphrase, my father pronounced his own surname with an Anglicized American dialect. “Jimenez” with a hard “J” sound. He used to have the guys at work call him Joe.

This decision can be traced back to my parent’s house hunting efforts on Long Island in the 1970’s. Red-lining was in full effect when their real estate agent explained their skin was light enough to pass in Levittown, as long as their name wasn’t on the mailbox.

My sister and I grew up monolingual; My parents’ attempt at protecting us from the growing racism faced by Puerto Ricans trying to infiltrate the suburbs. To survive Levittown as a Latine person was to blend. Passing for Italian or Greek was the goal. As a family, we celebrated our heritage through Menudo pajama dance parties and arroz con gandules but outside of our Saddle Lane cape home, we learned to assimilate.

Fast forward to the summer of 2000. Having just completed undergraduate theatre work, my wet behind the ears ass tried a career in acting. Enter three barriers to this goal: My weight, my Queerness, and my last name. A manager told me, “You’re fat and fey. Adequate enough for character roles, but Jiménez? What do I with that? You don’t speak Spanish and don’t look like a gangbanger. You should change your name.” So at 22, desperate to thrive, I changed my name. Christopher Julian Jiménez would now be J. Julian Christopher. White enough for systemic racism and non-descript enough to blend. The boy can leave Levittown, but Levittown will always live within.

I was cast in mediocre roles and continued on in grad school to hone my craft. Grad school was more of the same, frankly. I had a new crispy white name, but was told to do works by Paddy Chaefky rather than Jose Rivera. I was told to play straight roles otherwise forever be labeled the gay actor. I was told to lose 50 lbs, to play leading men. I did all of these things I was told and the work didn’t come. Now, I’m not so naive to think that perhaps I just wasn’t good enough, but how could I be good at anything while carrying the weight of shame about my body, my effeminate mannerisms, and my “non-descript ethnic” identity?

Once, I was cast in a Latine role and a reviewer wrote, “Played convincingly by Anglo-actor J. Julian Christopher, he is a street-hardened Latino…” Right there, branded in ink, my

identity crisis screaming at me, “You’re a fraud!” I didn’t want the perception to be I was pretending to be somebody else, but that was exactly what I was doing.

I began to write plays for myself, with characters that reflected my queer and anglicized Latine experience. I could examine these issues, shielded by artistry. And through my writing, which became my life preserver, I could speak my truth which brought me success through high-profile playwriting programs and productions. But when I attached my “approachable” name to the work, I still felt twinges of guilt. Was I a sell-out? An opportunist succeeding because of an easily pronounceable name? Sadly, that was probably the truth.

I’m calling myself out. How can I possibly write about authenticity when the name I attach to the work is anything but? I do not want to hold onto this 20-year old misleading moniker. At 22, I allowed white supremacy to permeate my being. We all fall victim to it but how we continue to address it is the indicator of our growth. I am extremely proud of the career I have built on the name J. Julian Christopher, but it is also a lie. J. Julian Christopher didn’t write those pieces. Christopher Julian Jiménez did.